In the late hours of November 21, the Labour MP for Derby made an impassioned plea to the House of Commons.

He urged the government to do their part within the international effort to provide sanctuary for vulnerable refugees, including unaccompanied children, caught up in Europe’s refugee crisis.

“There is not a Government in Europe today which is not already faced with cruel and urgent questions concerning refugees” he stated. “Where is this thing going to end? What is it going to mean to us?”

In agreement, the MP for Wolverhampton East said: “It is most important that Great Britain should firmly and strongly take the lead … and make it a major part of British policy to see that action is taken.”

Their speeches were persuasive. So persuasive, that – combined with the lobbying work of faith groups and civil societies – they moved the Home Secretary to waive visas for ten thousand child refugees.

Ten thousand young lives were saved from imminent danger.

The decision to welcome unaccompanied children to the UK was announced with a statement of hope from the Home Secretary: “Here is a chance of mitigating, to some extent, the terrible sufferings of their parents and their friends.”

If you are thinking this rhetoric sounds uncharacteristic for Priti Patel, you would be correct. These events unfolded more than eighty years ago, under a different Conservative government.

The Home Secretary in question was Sir Samuel Hoare, and his announcement led to a historic rescue effort providing a railway route to safety for thousands of children at risk from Nazi Germany, just nine months prior to the outbreak of World War Two.

The Kindertransport was born, and its incredible legacy is celebrated with pride today by British politicians across all major political parties.

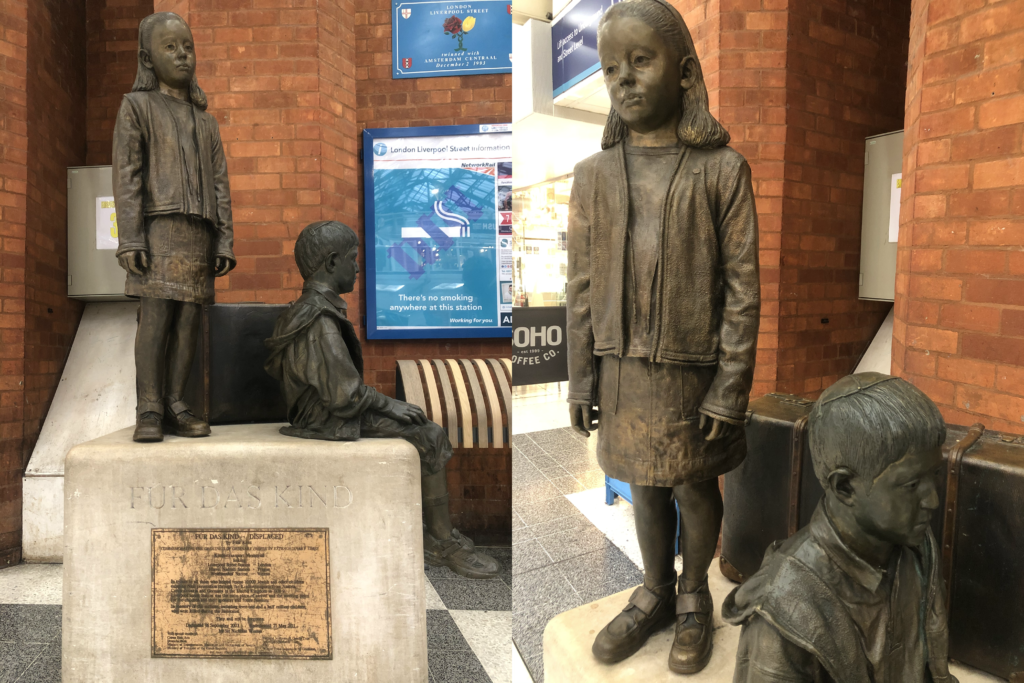

In the heart of London, bronze statues at Liverpool Street Station proudly depict the young children of the Kindertransport who would have arrived at the station in 1939; many would become the only surviving member of their family after the holocaust.

So what does this legacy mean to us in 2021? How can we, as a nation, keep celebrating our pride as a place of sanctuary while the proactive and compassionate commitment to safe passage for child refugees is steadily abandoned by our current government?

One boy who travelled to the UK on the Kindertransport aged six, from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, grew up to ask the government this very question. Repeatedly.

Born in Prague in 1932, Lord Alfred Dubs, who introduces himself as ‘Alf Dubs’, is a Labour Life Peer and former member of parliament for Battersea South. He describes his pivotal two-day journey to England, that would later inform his lifelong commitment to refugee activism.

“My mother put me on a Kindertransport train in June 1939” he begins, explaining that as a six-year-old boy he didn’t understand what was happening as he watched his mother wave him off at the platform surrounded by German soldiers in uniforms displaying swastikas.

“For many of the parents waving their children off that day, it was the last time they ever saw them.” Lord Dubs says he was one of the youngest on the two-day train journey to London, and only understood later why the other children cheered after day one when they reached the Dutch border: “They were cheering because we had reached safety from the Nazis.”

In 1937, two years before Lord Dubs’ train journey to the UK, Nazis had occupied his birthplace Prague. His Jewish father “disappeared immediately”, fleeing to England.

“We were told at school to tear out a picture of the Czech president Benes from our books and replace it with a picture of Hitler” he says, adding that his mother told him not to follow the other school children who had been instructed to attend Hitler’s victory parade in one of Prague’s main squares.

“I am reminded of something Tom Stoppard said about his family in Prague before the war” he says. “They didn’t think of themselves as Jewish until Hitler defined them as such.”

After a long two-day journey, Lord Dubs was reunited with his father at Liverpool Street station. He now campaigns tirelessly for other families to experience such a reunion.

“Britain saved my life, and it has been my home ever since. I am grateful to Britain in a way that I believe only a refugee can be. Today’s Britain, however, is a different place. It does not welcome child refugees.”

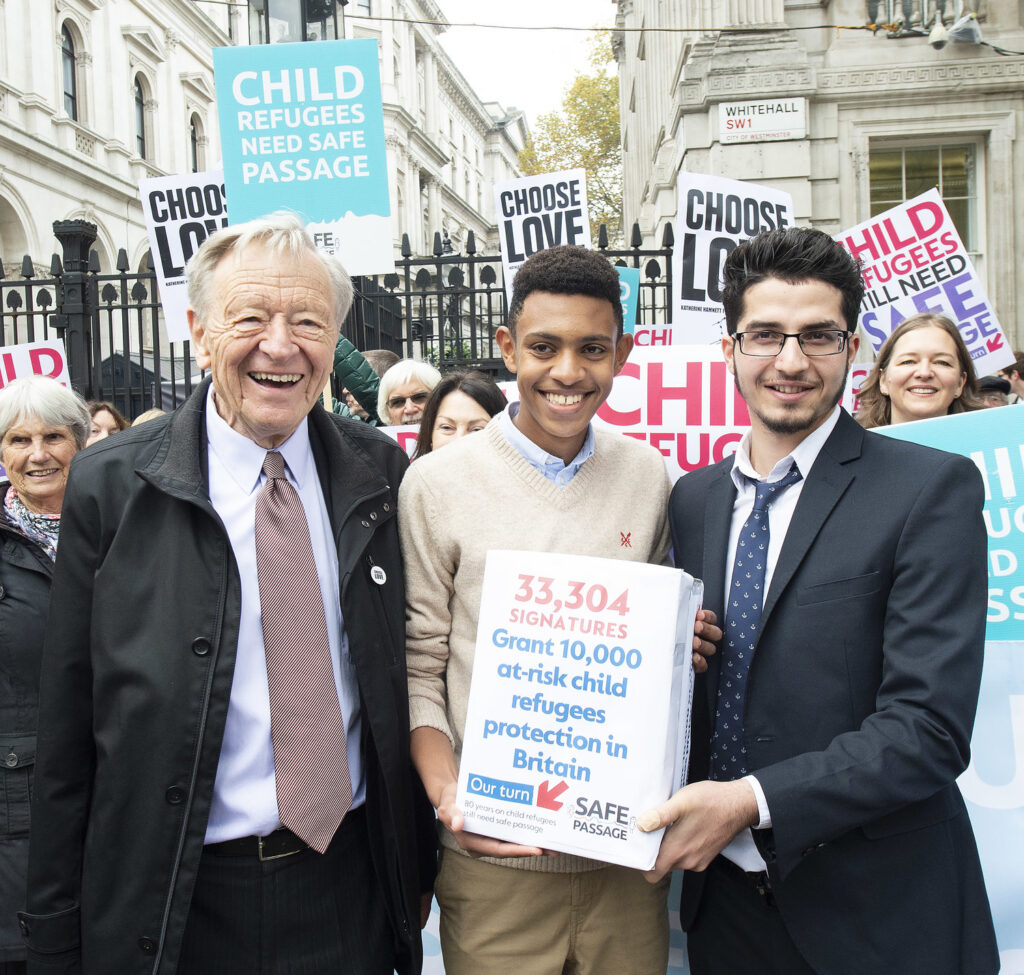

Earlier this year, Safe Passage, a child refugee charity that Lord Dubs regularly campaigns with, took legal action against the Home Office for their asylum guidance, which negatively affected the claims of child refugees trying to reunite with family members in the UK.

The High Court ruled in their favour stating in July that Home Office guidance was unlawful because it instructed caseworkers to refuse applications from unaccompanied minors after two months “even where inquiries had not yet established whether a family link existed and/or whether it would be in the child’s best interests to have their claim decided in the UK.”

This legal victory may have provided hope for some families, but unaccompanied children living alone in European refugee camps are no longer eligible to apply for family reunification in the UK: A government move that was heavily criticised by Lord Dubs and cross-party voices in parliament during debates on the Nationality and Borders Bill this week.

Home Secretary Priti Patel argues that the new bill, which many charities have labelled the “anti-refugee Bill,” will “break the business model of the evil people smugglers” by criminalising irregular entry into the UK.

Lord Dubs says the opposite is true, arguing that the government’s failure to provide safe and legal pathways to the UK for vulnerable people leaves the most vulnerable at the mercy of traffickers and keeps families apart.

The government’s own equality impact assessment of the bill similarly states that new plans could force people to take more dangerous journeys to reach safety.

“We have seen the chaos in Afghanistan and the circumstances under which Afghans are fleeing, even before the Taliban took control,” he says. “So, are we saying that unless someone is able to assemble and retain all documents and make an ordered and planned journey, that they are not welcome here?”

It’s clear that Lord Dubs sees the Home Office attitude towards refugees as deeply un-British. He states that government rhetoric about “floating walls in the Channel” and “deportations to islands in the South Atlantic” does a “disservice to Britain’s history.”

This December marks 83 years since the first Kindertransport children arrived in the UK, and Lord Dub’s 89th birthday.

After decades of campaigning, you may expect Lord Dubs to feel tired and defeated as the UK government dismantles “the very principle of asylum” according to several refugee charities like Refugee Action and The National Justice Project.

But, he rejects the idea that Britain’s humanitarian values are a thing of the past: “The arrival of the Kindertransport children in the UK was not without controversy” he says, adding that it was the British ideals of fairness that persuaded many British families to take in children from the Kindertransport who were without their parents.

“If Britain can do it then” he says: “Britain can do it now.”