Imperial College London researchers have come up with technology which allows them to patrol forests and measure environmental changes.

Scientists from Imperial College London have developed a solution for measuring climate change in hard-to-reach forests.

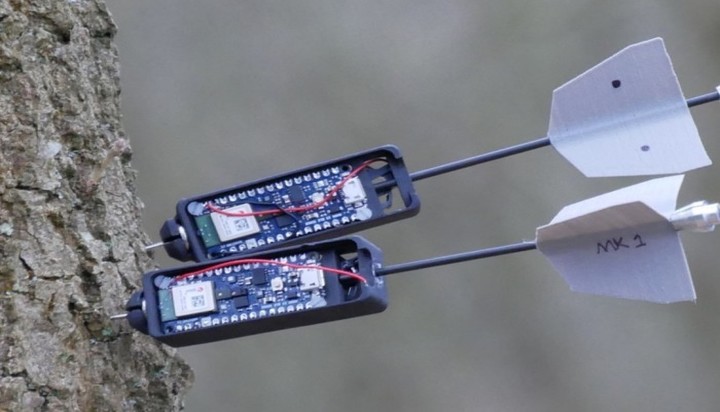

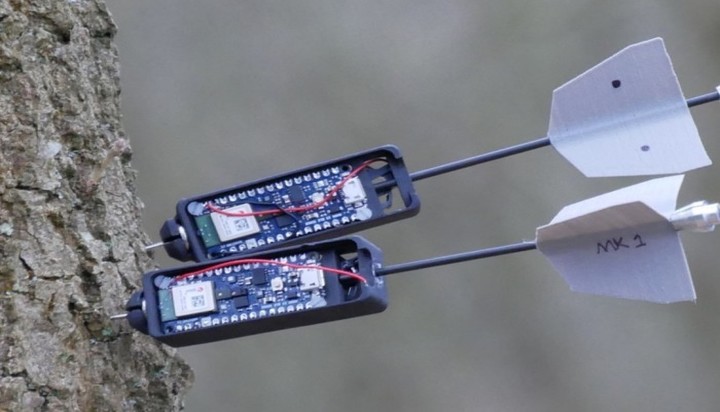

Drones that shoot darts loaded with sensors at trees, will soon fly around the world to assess the environmental impact of global warming on nature reserves and woodlands.

The flying devices designed by researchers from the Aerial Robotics Lab place sensors through direct contact or by perching on tree branches like birds.

Co-Author André Farhina of the Department of Aeronautics said: “The idea is to measure the climate variations in different parts of a jungle. Usually, the ecosystem of a tropical forest is totally different in various heights of the canopy.”

He explained that the UK might be an ideal country to test the new technology as there are a great number of parks and woodland that can offer valuable insights to climate scientists.

The sensors can offer data about specific values, including temperature and humidity.

The main goal of the project was to create a lightweight system that could be used in tropical forests and jungles to monitor the pace at which hard-to-reach natural environments change as a result of climate change.

The technology has already been tested on trees at Imperial’s Silwood Park Campus and the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology and could potentially be deployed in UK parks and forests even from the next year.

“There are a few challenges that must be addressed before the drones can be regularly used in forests,” said André Farhina from Imperial College London (Image: Raven News/ Zoom)

Mr Farhina added: “When the drone comes to the canopy, finds suitable targets and when the user gives the ok, the drone takes command, launches the sensor and after that, the pilot takes command again, and the drone can return to the base.”

What to target depends on the kinds of trees that need to be monitored and where specific trees are located.

Drones are also equipped with cameras that can show scientists maps of a given area. Based on this footage, they can then estimate the size of each forest area.

Image: “We aim to introduce new design and control technologies to allow drones to effectively operate in forested environments” said Dr Salua Hamaza from the Department of Aeronautics (Image: Raven News/Zoom)

Co-Author Dr Salua Hamaza, of the Department of Aeronautics, said the project started one year ago: “We believe that these kinds of technologies can not only be applied to forests. They can be used for maintenance of large infrastructure projects or for inspection of offshore plants.”

Dr Hamaza added that they could probably embed other types of sensors that could measure the density of some chemicals in the air, to prevent forest fires and other conditions that could put woodlands at risk.

She explained that one of the biggest challenges is to find energy-saving methodologies to enable drones to fly longer distances: “Drones, by perching on tree branches are currently able to stand there, and this gives us the opportunity to turn off the motors and save energy.”

The drones are currently controlled by people.

The next step is to make the drones autonomous so that researchers can test how they fare in denser forest environments without human guidance.

Lead researcher Professor Mirko Kovac, Director of the Aerial Robotics Lab from the Department of Aeronautics at Imperial, thinks of the drones as artificial forest inhabitants who will soon watch over the ecosystem and provide the data scientists need to protect the environment.

According to data from the University of Maryland, the tropics lost 11.9 million hectares of tree cover in 2019.

Almost a third of that loss (3.8 million hectares), occurred within areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for diversity and carbon storage. A report by the Global Forest Watch suggests the scale of the issue is equivalent to losing a football pitch of primary forest every 6 seconds for the entire year.

The 2019 data revealed that several countries suffered record losses – among them are countries with the highest number of different tree species, including Brazil and Indonesia.