What could have been an incredible multisensorial exhibition remained just a quirky, albeit enjoyable, exhibit.

Porcelain is notoriously fragile. Both in its wet state on the pottery wheel, a slight slip of the thumb can destroy hours of hard work. Later, in the limbo between being glazed and fired, the artist must be mindful of their every move. Finally, once out of the kiln, too, what might appear as a durable object can be shattered with just a tiny, imprudent bump.

I am reminded of this by the man at the door. “Please be mindful inside, you cannot walk too close to the pieces, the first room has some carpet on which you cannot step on and in the final room there is a work with liquid around it,” he warns me before I venture inside Strange Clay: Ceramics in Contemporary Art. That is a lot of instructions.

The large-scale group exhibition at Southbank Centre’s Hayward Gallery is the first in the UK to explore how 23 international and multi-generational contemporary artists have used clay and ceramics in strange and unexpected ways.

Though the warning initially makes me strangely uneasy, as soon as I step through the doors I am welcomed by a clash of colourful contours, an array of textures and theme subjects. It’s very busy inside and weaving through the other visitors, whilst also keeping a close watch of where my feet are, gets overwhelming soon.

The first room houses the colourful works of Jonathan Waldock and Betty Woodman. Waldock uses a variety of techniques to build tall, totem-like figures. Resembling huge, stacked mugs, he himself admits that the work, made to represent a series of historical periods that overlap, “might seem to be a relatively ludic affair” yet assures that it is “as unsettling as it is full of contradiction”. On the left wall, Woodman’s 1996’s House of the South vivid, abstract, seemingly broken 2D pottery pieces remind me of butterflies.

Indeed, strange is a fitting adjective. Odd, peculiar. These works seem to have come from a child’s dream. Just as I think this, I spot a couple of toddlers that, as two-year-olds often do, ignore their parents’ instructions and walk dangerously close to the artworks, before being quickly snatched up in their mother’s arms. I reckon that this will be a stressful afternoon for both of them.

I cannot help but sympathise with those tiny humans and think that this is precisely how art should be enjoyed, by everyone.

Sculpture allows for a variety of physical possibilities, an amazing opportunity for art to be entirely accessible. This opportunity was not seized.

Dr Cliff Lauson’s impeccable curation has each room’s work tie seamlessly with one another but the black tape, the limitations, the gallery assistants breathing down your neck all limit the visitors in their experience of the art pieces.

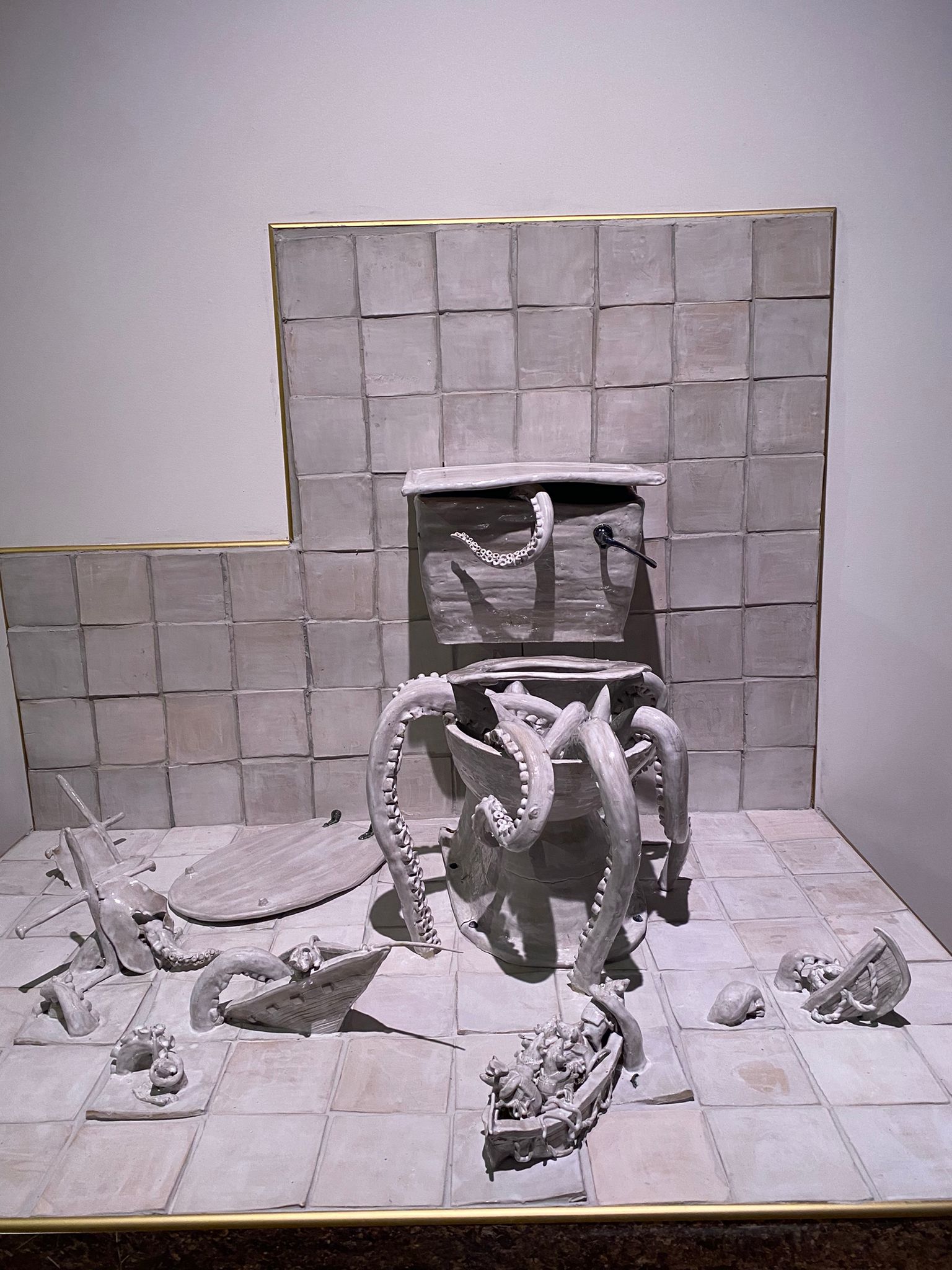

In fact, one room in particular clashes with the rest, precisely as it allows for a 360-degree approach to sculpture. Lindsey Mendick’s incredible Til Death Do Us Part is a commentary on the private wars that take place in relationships. Taking up the whole room, Mendick stages a different warfare in each room of the house, gory ceramic sculptures of mice, roaches, and moths attack each other relentlessly. Her work is multifaceted and multi-layered but, most importantly, it’s accessible.

Immediately the toddlers from before appear more engaged. There is music playing from a ceramic radio, bursting pipes hiding tiny spiders planning cyber-attacks on equally tiny computers, daily objects recreated in clay. Bright colours, changing textures, and no tape on the floor to indicate where one can or cannot step.

Mendick’s room is a breathing space, a respite from harsh overhead lighting and overbearing gallery assistants breathing down your neck. It’s an opportunity to engage with art with all your senses.

Borrowing the words of blind writer and artist Maud Rowell: “it matters that art, which touts itself as open and accessible to all, is not. […] Relying purely on sight to experience most forms of art cuts us all off from an entire sensory world which could enhance our understanding and appreciation of culture.”